Part I: Fundamentals

Hello! You’re reading Ben’s Guide to Software Development, the weekly bulletin where I post draft chapters of my upcoming book, Process to Processes. You can read everything I’ve written so far by clicking this button:

Now that I have a pretty solid draft of the Preface, I’ve started fleshing out the first section of the book proper. I’m calling it “Fundamentals” instead of “Introduction” because I suspect no one reads introductions, and this initial section might be the most important one in the book — in the sense that you can derive everything else from it, with a little effort (okay, a lot of effort).

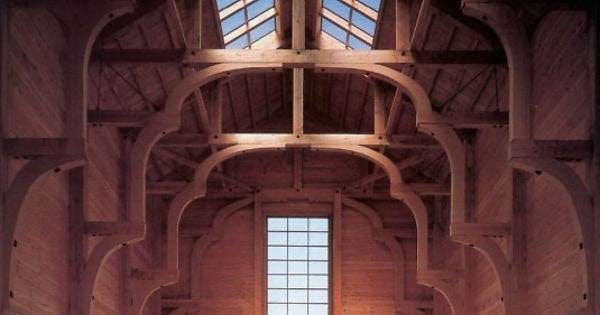

Today’s missive is the two-page summary that begins the “Fundamentals” section. Fans of the architect Christopher Alexander will no doubt recognize his influence here. The idea of Forces is straight out of Notes on the Synthesis of Form; Centers and Feeling are from The Nature of Order. The principles of Small Steps, Fast Feedback, Adaptation, and Autonomy pervade his work. If you’ve read Alexander, maybe you can let me know how well I’m presenting his ideas? And if you’ve never heard of him, I’d love to get your perspective on whether my hasty summary of 4,000 pages of his writing makes any sense. Let me know in the comments on Substack, or in reply to this email.

One of my goals for this section is to broker peace (or at least a truce) between software developers and management. I truly believe that human-centered ways of making software are in everyone’s best interests1 and the sooner we all agree on that the better off we’ll be. So if you’re a manager: do I at least hint at a compelling business case for this? Is there anything you find alarming? I hope you’ll let me know.

Fundamentals

The subsequent sections of this book will interest different audiences. Programmers may want to start with Changing Code Within One Function; managers with Working on a Team; UX designers with UserInterfaces. However, everyone should first read this section, Fundamentals. Otherwise, the rest of the book will probably be inscrutable.

We’ll start with an overview of the types of information you’ll find in this book — Techniques, Principles, and Views.

Then we’ll dig into the foundations of empirical software development: Empiricism informed by Judgment, an ability to ExplainWhy we do things, and a healthy irreverence toward tools, techniques, and methods — ToolsNotRules.

Next, we will look at the constraints that shape every software project, starting with our own inherent limitations and abilities (Humans, Not Humanoids). We’ll learn to see our human-computer Systems as InformationFlows among Centers, and we’ll see how friction in those information flows reveals Conflict between the Forces that shape the system.

We’ll then turn our attention to the process of improving the system. A healthy system runs smoothly and efficiently; healing the system means removing resistance from InformationFlows. To do this, we must find ways to resolve the Conflicts between Forces. But this requires very fine Adaptation of every part of the system to its context, and that is difficult to achieve. The forces involved are usually so numerous and interrelated that analytical approaches to balancing them are prohibitively expensive.

The solution is to leverage one of our Human strengths: the massively parallel data-processing ability we call Feeling. By taking part in the system — by actually being in an information flow, or else working very closely with the people who are in it — we can immediately sense the pain points. If we can then prototype changes to the system and experience the results more or less immediately — SmallSteps, FastFeedback — we can start to improve things very quickly.

To be able to do this — and to do it over and over, rapidly enough to keep up with the system as it evolves — the people who are actually in an information flow must be empowered to improve it. In other words, we need Autonomy, the freedom to “think globally and act locally.”

But of course autonomy isn’t enough. We also need the skills and wisdom to act effectively, and avoid damaging the system. Otherwise, autonomy will only sow chaos. Autonomy does not mean “move fast and break things,” as Mark Zuckerberg memorably put it. Rather, we want to move gracefully and mend things.

Move gracefully and mend things.

How can we gain the skills we need to do this? We can’t take years off to study. We have to learn on the job. But we also can’t transform our workplaces from zero to “full autonomy” overnight. If, by some miracle, we manage to convince our employers to let us do so, we’ll almost certainly make a mess, and they won’t give us a second chance.

The Gordian knot may seem firmly tied, but there is a loose end we can pull at. The reality is that we already have a certain amount of autonomy — in the act of typing code, if nothing else. We can use that to bootstrap the system to higher levels of autonomy, by improving what we can and reliably delivering results. Success earns Trust; we can turn increased trust into increased autonomy. As we grow in our abilities, untangling larger and larger loops of the system, our transformations will extend to architecture, team structure, project management, user interface design — and perhaps beyond.

Table of Contents

Techniques

Principles

Views

Principle: Empiricism

Principle: Judgment

Technique: Say Why

View: Tools, Not Rules

View: Humans, Not Humanoids

View: Systems

View: Information Flows

View: Centers

View: Forces, Not Requirements

View: Conflict

Principle: Adaptation

Principle: Fast Feedback

Principle: Small Steps

Principle: Feeling

Principle: Autonomy

Technique: Build Trust

…subject to some caveats which I might discuss in a future post. Basically, a lot of software gets funded in exploitative, dare I say scammy ways. (Often it’s investors who are getting scammed.) Better engineering isn’t going to fix that; indeed, I think it’s probably incompatible with it. Scams rely on information asymmetry; improving information flows runs directly counter to that.