Readme-driven development

My first forays into programming, in middle school and high school, were in the domain of computer games — written in Visual Basic, of all things. I had limited access to the family PC, so I spent a lot of time away from the computer daydreaming about the next feature I would build for this or that game.

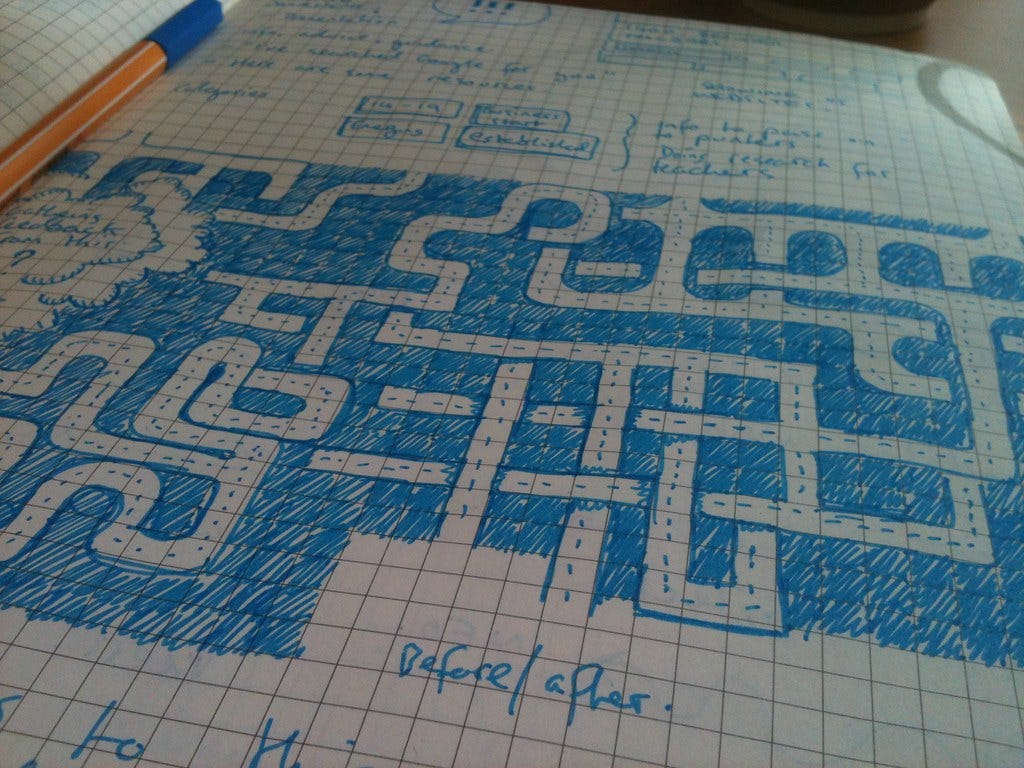

I recorded my ideas in the form of user manuals, even going so far as to draw “screenshots” of what I imagined the UI would look like. This seemed natural to me, because at the time, a lot of games did have lavish, illustrated user manuals. Two of my favorites were the manuals for Sim City 2000 and F/A-18 Korea. These were the touchstones that I tried to emulate as I wrote detailed tutorials and reference documents for imaginary games — many of which I never actually built.

I’m sharing these memoirs in the hope of convincing you that writing documentation can be fun. In fact, if you’re not careful, it can turn into a guilty pleasure. Writing documentation for programs that don’t exist yet gives you a feeling of accomplishment for less effort than it would take to write working code. But it’s also useful: documentation helps you plan the implementation.

Your pre-implementation docs don’t have to be elaborate. In fact, it’s better if they’re not, because your plans will almost certainly change. That’s why the technique we’re discussing today is called “readme-driven development” and not “documentation-driven development.” A readme is the minimum viable documentation to get your project off the ground.

Plans are worthless, but planning is everything.

How to begin

README.md is often the first file I create in a new project. Before I have any code, I write a bit of prose about what exactly I’m going to build.

What goes in a readme varies by project, but I usually start with:

An explanation of what the project is and why I’m doing it. What problem does it solve? What’s unique about it? What will make it stand out from the competition? (Technique: Say Why)

A sketch of a user manual. How do you install the thing? What’s its public interface?

High-level thoughts about implementation, e.g. data formats and architecture.

Developer documentation. (See: Walking Skeleton)

Why

Starting with a readme…

helps your team agree on what you all are going to do before you do it.

provides the basis for a backlog of user stories.

reveals flaws in the design early, when they’re easy to fix.

records your ideas — they may be valuable later, even if you don’t end up implementing them in the first version.

grounds your designs and keeps you from accidentally straying from your original vision. (You can, of course, intentionally change your vision later.)

ensures you write documentation.

Pitfalls

Don’t fall into the trap of gold-plating your readme. Remember that it’s supposed to be concise and low-polish. Avoid getting too committed to your early plans — they will change.

Another possible failure mode is that you make plans that are so ambitious they turn out to be unimplementable. The readme-writing phase of a project is a good time to dream big, but perhaps not too big. Remember, you are going to have to build this thing. So make grand plans, by all means, but hold them very loosely. If you share the readme with people outside your immediate team, be sure to communicate that it is aspirational — a highly speculative rough draft. Put prominent notices to that effect in the readme itself.

As soon as you run into implementation difficulties, consider whether a different design would be more feasible, or whether you can ditch the feature entirely. My motto is: never hesitate to cut scope. You can always add it back later.1

Examples

Here are some first drafts of readmes I’ve written for my projects:

It’s fun (for me) to look back at these old readmes and see just how much has changed about the design of the programs they’re supposed to document. Half the features described in the original mdsite and audition readmes either got scrapped or were implemented differently. Even so, writing these readmes was extremely helpful for clarifying my thoughts and planning implementation.

In a few of my projects, writing the docs was the fun and valuable part, so I stopped there:

One of my favorite examples of a successful project that had to cut scope is the game Heroes of Might and Magic IV. Rushed to production as the studio was running out of money, it is the flawed-yet-beautiful end result of a series of thoughtful compromises.