Steps Under the Microscope

We change a software system by taking many small steps to get from our current state to our desired state. GeePaw Hill defines a step as:

a purposeful gap of unreadiness between two points of readiness on some system’s timeline, a before point and an after point.

The system starts ready, and it ends ready, and the step is that period during which it’s not ready.

This definition is precise, but pretty abstract, so today I'd like to talk about what steps mean to me in practice.

An Example

Say we’ve just created a brand new file and rolled up our sleeves to write some TypeScript. The system is in a ready state, because an empty file is perfectly valid, runnable TS, even though it doesn’t do anything.

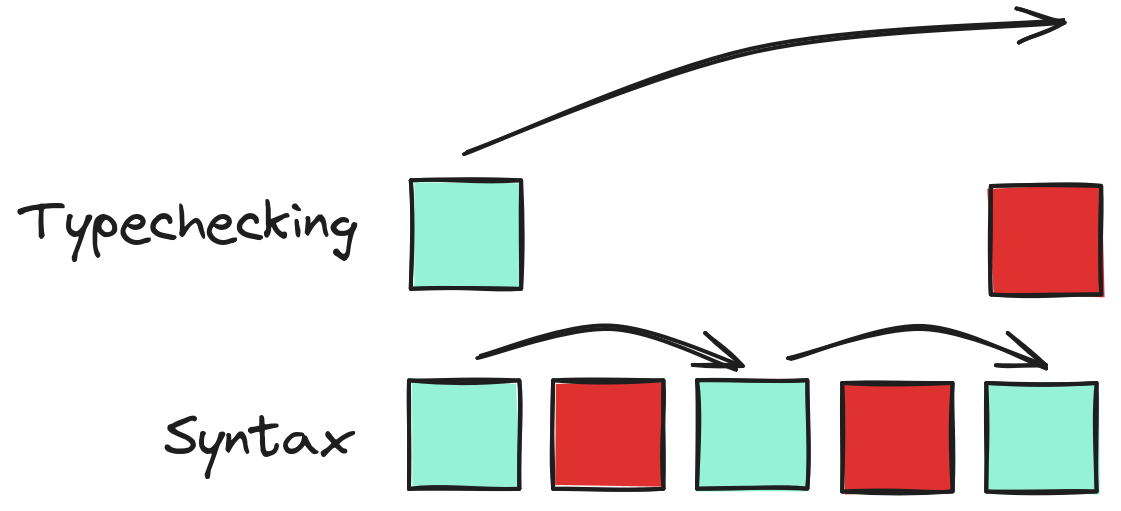

I’ll represent this ready state as a blue-green square.

Now we want to import our test framework so we can do some TDD. By the time we’ve typed

importour system is no longer ready. This isn’t syntactically valid TypeScript, because import is a keyword and needs to be followed by whatever we’re importing. At this point, we’ve taken half a step. We’re up in the air.

We finish typing the import statement, and we’re back on solid ground again. Ahhh. Relief. That’s one step.

import {test, expect, is} from "@benchristel/taste"We take a few more steps of this kind, completing our first test:

import {test, expect, is} from "@benchristel/taste"

test("a Calculator", {

"initially displays 0"() {

const calculator = new Calculator()

expect(calculator.display(), is, "0")

},

})But now, a funny thing happens. We’re in a syntactically valid state, but our code doesn’t typecheck, because Calculator is not defined. Although we’ve taken many steps at the syntactic level, we’re now just halfway through a step at a higher level — the level of types.

There are a few ways we could get back to green, but the quickest is probably to define Calculator in our current file.

import {test, expect, is} from "@benchristel/taste"

class Calculator {}

test("a Calculator", {

"initially displays 0"() {

const calculator = new Calculator()

expect(calculator.display(), is, "0")

},

})The typechecker still isn’t happy, because there’s no display() method. Let’s add that.

import {test, expect, is} from "@benchristel/taste"

class Calculator {

display() {}

}

test("a Calculator", {

"initially displays 0"() {

const calculator = new Calculator()

expect(calculator.display(), is, "0")

},

})And now, both the parser and the typechecker are happy. Step complete!

…except, the test fails.

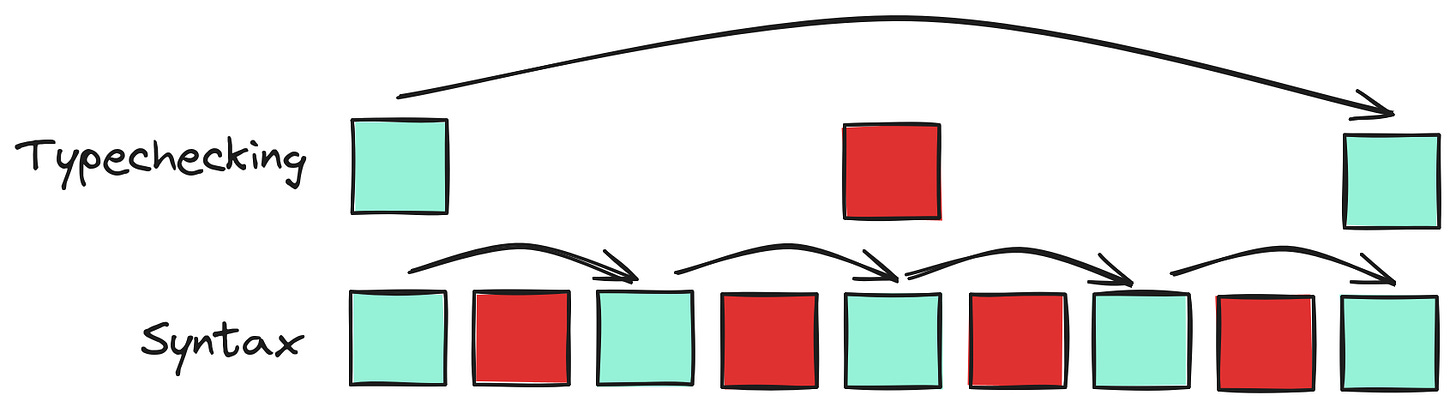

Getting the tests to pass is pretty easy: return “0”. I’m getting kind of tired of drawing these pictures, but here’s a final view of our journey from green to green.

Debrief

I think you get the idea. We take steps at multiple levels of scale, using multiple layers of verification that tell us how “ready” we are to ship software.1 The smallest scale, and the most primitive type of verification, is syntax checking, and at that level we can flicker back and forth between ready and unready many times per minute. The next smallest scale (in static languages) is typechecking or compilation. It takes a bit longer to go from green to green at that level. Then come tests, and perhaps linting, and beyond that commit-readiness, integration-readiness, and release-readiness. We’re not “ready ready” until every level is green.

The point

The smaller we make our steps, the smoother and safer our work becomes. Smooth and safe are prerequisites for fast. This is true at all levels of scale.

When we’re halfway through a step, in the unready state, we’re a lot less maneuverable. Changing course is risky because the unfinished work is likely to get in our way and trip us up. In the ready state, we have a chance to get our bearings and figure out which direction to go next. If we don’t get back to ready frequently, it’s easy to get lost.

We’ve all experienced what happens when we get too far from “ready,” e.g. when we spend half an hour typing without ever stopping to compile. When we finally decide to run the code, we get: Syntax error. Syntax error. Type error. Syntax error. Type error. Oh, look, all the tests fail. In the best case, we spend a lot of time debugging. In the worst case, we decide the mess is too big to clean up, and we throw away our changes and start over.

Note: starting over isn’t always a bad thing; sometimes we “plan to throw one away” (as Fred Brooks put it) to learn more about the problem we’re solving. But wandering away from “ready” and getting lost in the weeds isn’t a strategic sacrifice; it’s just a blunder.

A similar problem can happen at the larger scales of software development. If you spend too long working on a feature without getting feedback from potential users, you’re liable to build something they don’t even want.

Keep your steps small, at every level of scale, and you’ll be a happier, more productive programmer.