Hello and happy new year! You’re reading Ben’s Guide to Software Development. This post is a continuation of the previous one, describing the codebase organization approach I’m calling “diamond design.”

Recap

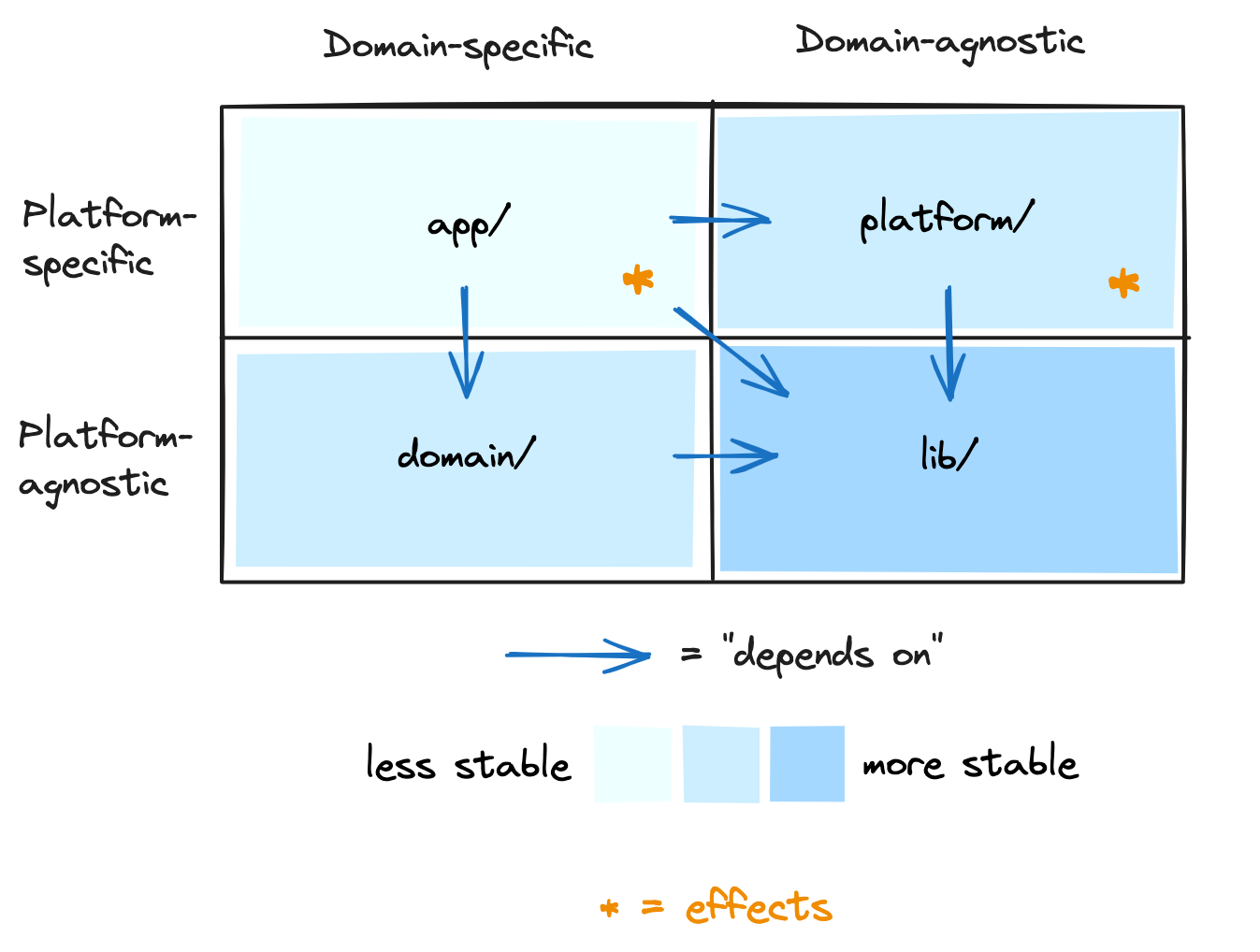

In part 1, we discussed the app/ and lib/ folders, which form the top and bottom “layers” of our program. lib/ is at the bottom and can’t call any of the other layers. app/ is at the top and contains the glue and user interface code that holds everything else together.

In this post, we’ll cover the stuff in the middle: domain/ and platform/.

Errata in Part 1

Ignore the stuff I wrote about code organization within subfolders of app/ and lib/. My actual codebases break these “rules” all the time, and I’m not sure how valuable they are even as general guidelines. I’ll need to think about this topic a bit more.

Domain and business logic

Domain logic is the core of our application. Domain code is arguably the most important code we write, because it defines the concepts and behavior that users care about.

In a music production app, the domain code talks about tracks, notes, instruments, and samples. In a financial planning app, it’s all about currencies, budgets, interest rates, and stocks. In a language-learning app’s domain code, you’ll find vocabulary, lessons, spaced repetition strategies, and practice exercises.

Domain code is platform-agnostic. It doesn’t know or care where our code runs (a web browser? a smart TV?) or how it presents itself to users (a command line interface? A GUI?) It can get away with that because it just defines data types and the operations on those types.1 It doesn’t know about the user interface or about data persistence.

Some people like to distinguish “domain logic” from “business logic.” AFAIK, the difference is that domain code concerns itself with what is logically possible, while business code concerns itself with what is allowed by policy. For example, in a social media app, the statement “A follows relationship is between two accounts, the follower and the followee” describes the domain, while “A user can follow no more than 500 accounts” describes a business rule.

If we wanted to uphold this distinction in code, the “follows” relationship would be implemented in domain/, while the 500-followees limit could be implemented in app/ (possibly in a web controller or service layer) or possibly in its own business/ layer between app/ and domain/. I’ve never bothered making this distinction in my programs, though, and can’t say I have a strong (or particularly informed) opinion about it.

Platform code

Now let’s switch gears and talk about platform code. Platform code is the polar opposite of domain code. Just as domain code knows nothing about the platform, platform code knows nothing about the domain. That enables it to be reused between applications with different domains.

I define “platform code” as encompassing everything that

makes the program available to users: the UI technology, the installer, the web framework, etc.

connects the program to the real world, via effects.

Examples of platform code include:

The event loop for a GUI app or game

Routines for reading and writing files

A SQL query builder

A web server framework

A suite of React components implementing your company’s design system.

Why separate platform code from domain code? One reason is to ensure that your most valuable code — your domain code — is platform independent. Platform independence gives you amazing flexibility. It’s why, for instance, the TypeScript compiler can run in a web browser, even though it “normally” reads code from a filesystem. The part of the code that knows about filesystems is strictly separated from the part that knows about TypeScript syntax and semantics, allowing the second part to run without the first.

Summary

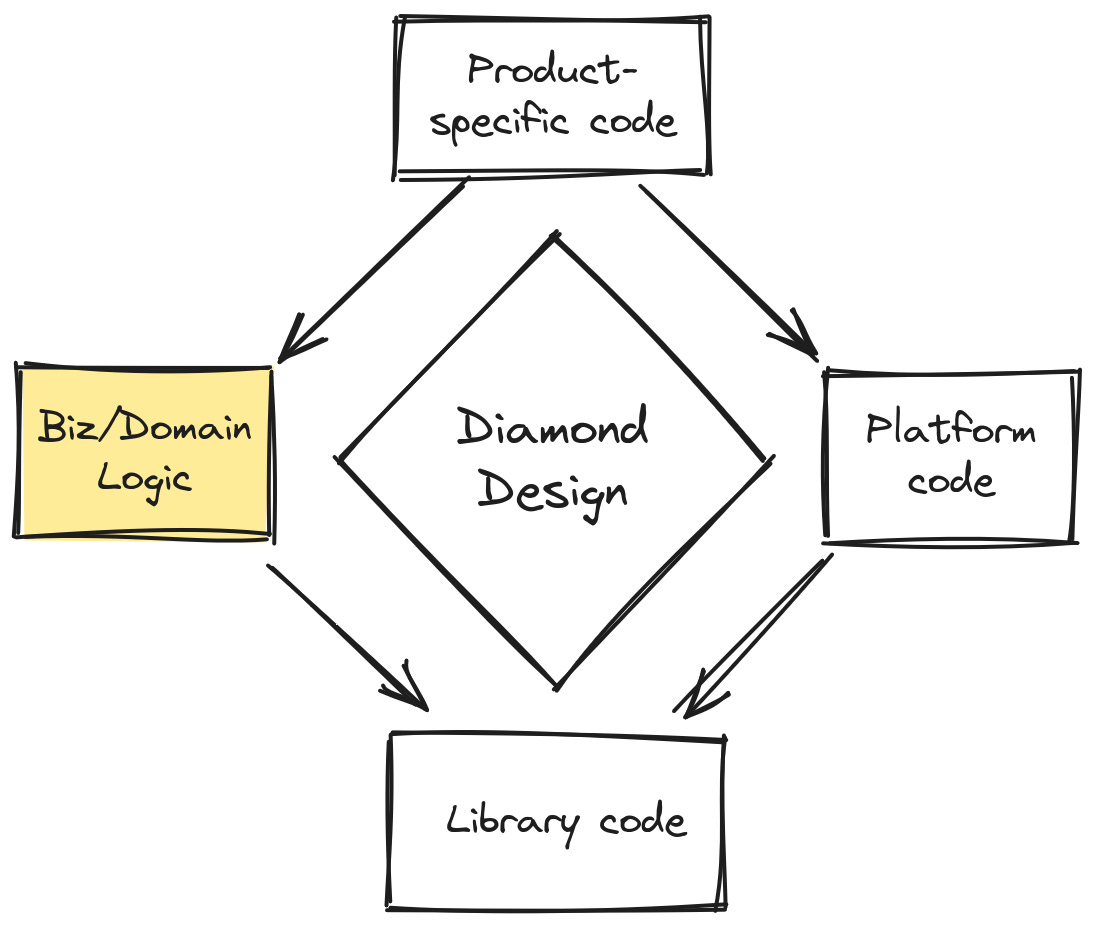

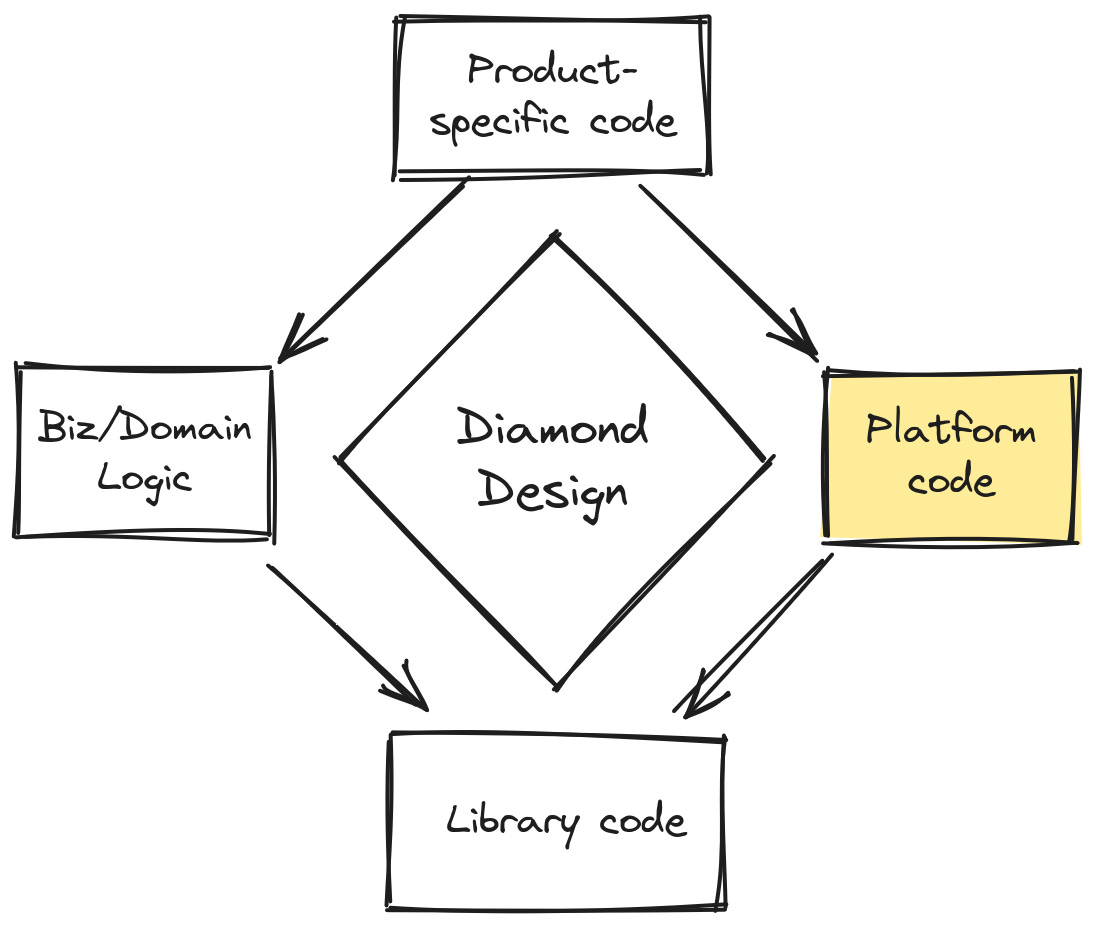

Here’s another visual summary of the different types of code in diamond design:

Why diamond design?

There are several reasons you might choose to adopt something like diamond design in your applications. I’ll briefly touch on a few of them here.

Encoding knowledge

I have come to see software development as a special case of “teaching systems how to do things.” Whenever I learn something or figure out how to do something, I want to put that knowledge into the system — encode it into the system — so that the system as a whole will remember how to do the thing I just did even after I’m gone.

Elsewhere, I wrote,

To build steadily on our abilities, step by step — that is the goal of engineering.

The idea of “building on our (collective) abilities” implies a shared pool of knowledge from which we can draw. In order for this knowledge to be legible and reusable, it has to be organized. Diamond design provides that organization.

Suppose, for example, that I figure out a neat way to solve some platform-level problem, e.g. making paginated database queries. If I then encode that knowledge so the platform-level logic is intertwined with application-specific code, I’ve missed an opportunity. No one else can reuse my code as-is, and it may take some effort to reverse-engineer my discovery. Although I’ve solved my immediate problem, I’ve failed to expand the system’s capability to solve future problems.

If, on the other hand, I carefully separate the different types of code, each part becomes easier to understand and reuse. The system is then better able to adapt to new needs.

Work styles

Each type of code in Diamond Design benefits from different techniques, different views, and even different attitudes. Separating them gives programmers a clearer sense of how to behave around each type of code.

App code tends to be “move fast and break things.” Nothing else depends on it, so it’s free to change. Lib code, by contrast, needs to be “slow and solid,” because it’s the foundation for everything else.

Platform and app code can be hard to unit-test due to their effects, so they must be kept “too simple to break.” Type checkers can help seal the testing gap, by verifying that app code wires its dependencies together correctly.

Domain code, on the other hand, can and should be thoroughly tested. It might also benefit from review by nontechnical folks. To hear Scott Wlaschin tell it, domain experts are often perfectly capable of pointing out bugs in a set of F# type definitions.

Bonus facet: formats/

The four-way distinction between app, domain, platform and lib code makes for pretty pictures, but in practice I have found myself adding a fifth category, for code that deals with serialized (i.e. stringified or binary) data representations which are persisted to disk or sent between processes.

Here’s how formats/ fits into the picture:

Code in formats/ consists of pure functions, without effects. These functions are of two types: parsers and formatters. Parsers take the serialized representation and convert it to the in-memory domain/ model. Formatters go the other way.

“Why not just use JSON.parse()?” you might be thinking. And you have a point. When a program is new, there’s little motivation to create bespoke parsers and formatters. You just use whatever facilities your language has built in to convert your domain objects to and from a serialized format and that’s that.

But what happens when the domain model changes, e.g. to add a new field to an object? When you parse data created by old versions of your program, that field will be null. So you’ll have to change your code to handle nulls.

It’s easy enough to give a missing field a default value, but you want to have a central place for the logic. Otherwise, it will get duplicated all over your codebase and create a mess. The formats/ facet is that central place. As your data format accumulates more changes, you’ll probably end up wanting a versioning system, and the ability to migrate old versions of the format to the latest. formats/ is the place to deal with all that.

The overall purpose of formats/ is to shield your domain model from the grimy details of persistence, and ensure that it does not need to battle the ghosts of its past selves in the form of legacy data. You want your domain code clean and pristine, and formats/ allows it to be so.

A common mistake with formats/ is to make the domain code depend on the formatting code instead of the other way around. That compromises the purity of the domain code, though, and complicates things if you ever have multiple formats you need to write. So it’s better to arrange things as in the diagram above.

You probably won’t need formats/ if all your data is in a relational database you can run migrations on. If it’s stored in files, though, or a NoSQL database, you’ll need parsers and formatters sooner or later.

What am I missing?

As I mentioned, Diamond Design is only a half-baked idea, and I’d love to hear your feedback and suggestions. How do you organize your code? Let me know in the comments (on substack) or in reply to this email (if you’re reading this as an email).

Further reading: Domain Modeling Made Functional by Scott Wlaschin.

This is awesome, Ben! I especially love the formats/ concept. I'd like to hear more about how this code is structured. Is it essentially a glorified set of helper functions? Shims to throw in after every JSON.parse?_